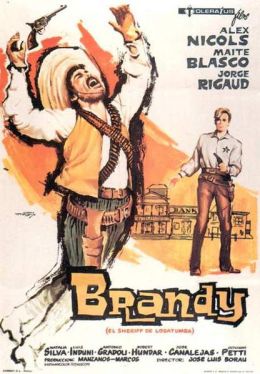

Neat Shot: José Luis Borau’s Brandy

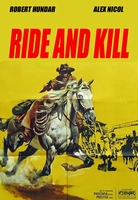

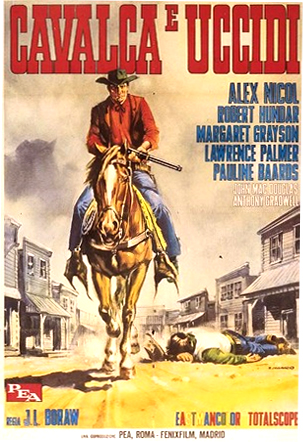

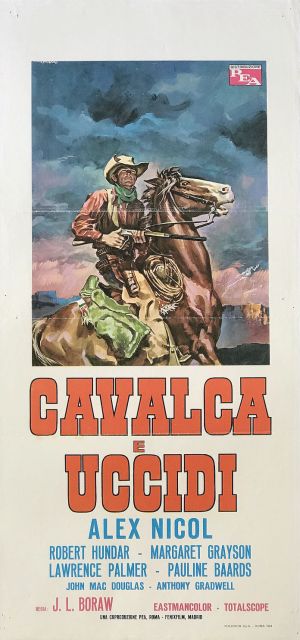

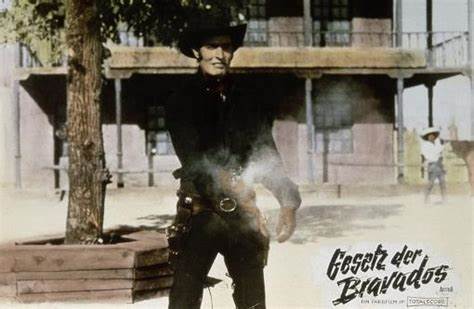

Like Tequila Joe (1968 / Dir: Vincenzo Dell' Aquila), José Luis Borau’s Brandy takes its eponymous lush and grants him title status. In the case of the latter, this is a good thing, as the film itself seems unsure – confused, even – as to who, exactly, the film’s de facto hero is. In France, the film was released as Pour un whisky de plus, which – tellingly – implies the importance of a general distilled alcohol more integral to Borau’s film than the so-called protagonist. The English language release went by the more apt Ride and Kill, a much more genre-friendly (albeit generic) title. Produced by Alberto Grimaldi’s Produzioni Europee Associati (PEA), Brandy is an Italian/Spanish co-production which, happily, feels far more akin to that early clutch of fascinating Spanish westerns lensed prior to Per un pugno di dollari throwing out the rulebook. PEA promised a slightly higher calibre of production – at least in terms of budget and distribution – when compared to the average Euro-oater, and by the early sixties had co-produced a number of significant European westerns, including The Sign of the Coyote (1963 / Dir: Mario Caiano); The Implacable Three (1963 / Dir: Joaquín Luis Romero Marchent), featuring Paul Piaget, Raf Baldassarre, Robert Hundar and Fernando Sancho; and I due violenti / Texas Ranger (1964 / Dir: Primo Zeglio), with the all-star line-up of George Martin, Frank Braña, Cris Huerta, Luis Induni, Aldo Sambrell and Antonio Molino Rojo. Each of those films are now recognized, to varying degrees, as being important bricks in the foundation of the European western. Brandy might be the least known of those early PEA productions, however; as of writing, Borau’s film is yet to receive a legitimate physical media release or ignite anything approximating a renewed fervour or positive reappraisal within the fan community. That’s a shame, as whilst the film is no lost classic, it does enough right to warrant certain rediscovery. (NOTE: This might be soon-rectified, however, as Brandy is now due to be released on DVD in Germany from Pidax Film, in July 2023, under the title Gesetz der Bravados. Our release calendar informs us that the film will be in widescreen, with German, Italian and English audio options, and have a run time of some 85 minutes – a cause for fan celebration even though no HD release.)

There remains, however, the small matter of ownership with regard to the film’s actual director. El Coyote author and regular screenwriter José Mallorquí is often cited as director, but this seems unlikely, whilst Mario Caiano is often credited as co-director, but I see no overt evidence of Caiano’s stamp on the film, either. José Luis Borau would appear to be the true director of the film, then (see film historian Matt Blake’s excellent book Spanish Cult Cinema, Volume 1: 1960 – 1964 for an extended discussion on said subject). The esteemed Borau would go on to enjoy a long and acclaimed career within the international film industry: his 1975 film, Furtivos, would win best film at the San Sebastián International Film Festival, and Borau himself would win Best Director award at the 2001 Goya awards for his celebrated drama, Leo (2000). In-between, Borau also directed the 1983 American film On the Line, starring David Carradine, Scott Wilson, and Victoria Abril, a decent-if-unfocused drama which plays out like a more grounded version of Walter Hill’s Tex-Mex thriller Extreme Prejudice (1987). Incidentally, one of Borau’s credited producers on that film, Antonio Isasi-Isasmendi, directed the 1960 Spanish western, Sentencia contra una mujer, which featured an early genre role for Antonio Molino Rojo. All roads, it would seem, lead back to the Euro-western.

It's also worth noting that the Spanish version of Brandy and the English-language release of Ride and Kill are slightly different films. The former has a runtime of 82 minutes, whereas the latter clocks in at a slightly longer 88 minutes. However, just to muddy matters further, the shorter Spanish version (Brandy) is not simply cut or edited down, but contains additional scenes not present in the international version. Likewise, Ride and Kill has entire sequences missing from the original version. It is, as they say, complicated. What follows is a short list of differences between the two films. (Note that this article is based on two very different print sources: The Spanish cut of Brandy is from a bootleg DVD-R of middling picture quality, a composite of English dub and un-subtitled original Spanish language tracks. This version, however, retains its original Techniscope 2:35:1 widescreen format. The international cut of Ride and Kill is an extremely compromised, heavily cropped VHS rip currently found on Youtube, English dub with no Spanish audio.)

Brandy (82 Minutes)

- No prologue. Animated title sequence in Spanish

- The Spanish version includes a number of detailed intertitles throughout the film, white font against red background, which seemingly act as chapter marks or narrative filler. The first of these seems to date the film as taking place in 1880 (although the extremely murky PQ makes it difficult to guarantee)

- A slight extension of the scene prior to Underhill, the banker, unveiling his new safe (Spanish audio only)

- At around the 50min mark, there is an entirely new scene inserted in which Stauffer, the honest judge of Tombstone, is visited by his wife, who appears to plead with her husband to continue his fight against the corruption in town. By this point in the film, the Judge is clearly despondent and losing faith in the justice system he works so tirelessly to uphold. This is a substantial sequence, almost three minutes in length, beautifully shot, with the focus on the wife throughout

- An extended sequence during/after the sheriff’s funeral, in which the honest townsfolk appear to collude and tentatively plan their burgeoning resistance. Whilst the majority remain somewhat reluctant, the young would-be deputy, Chico, seems most intent on taking a stand

- The fight scene between Donnelly and Moody’s henchmen – a major set-piece and overall standout sequence of the film, see below – is missing, cut from this version in its entirety(!)

Ride and Kill (88 Minutes)

- Credits in English over live action of bandits riding. Identical music score from Ortolani, however

- Short prologue in which Moody’s bandits appear to attack and kill a group of farmers/landowners. There is some good stunt work on show here, including an impressive horse fall

- No intertitles or chapter markers

- The aforementioned additional scenes from Brandy are missing here

- Most significantly, the sheriff’s funeral cuts straight to the saloon, where Donnelly fights off multiple attackers in an extended, highly impressive brawl (detailed later in this article). This is an exceptional action scene, allowing long-time genre staple Louis Induni a rare moment in the spotlight, and the actor proves himself to be a terrific physical presence

Whilst it’s always edifying to see a film in varying versions (if available), I have no preference as to which is the superior cut. It’s a travesty that Brandy loses the saloon fight sequence, but it gains that wonderful scene in which the judge is spoken to by his wife by way of compensation. Both work remarkably well. With that in mind, what of Borau’s film itself? (Note that the bulk of the following review will be based around the international version, Kill and Ride, but that I will refer to the film as Brandy, and continue to compare and contrast the two versions where appropriate.)

Borau’s film begins in standard fashion. The opening credits are rushed, perfunctory, no character (although there is an on-screen credit for microphone technician[!], which might be a first). In fact, the difference in on-screen credits is interesting. In the Spanish version, Frank Braña is listed amongst the cast, although I ashamedly failed to notice him on multiple viewings (the SWDb has him listed as Wagon Driver). Also, the actor Mark Johnson, playing the young would-be deputy, Chico, receives a special ‘Introducing’ credit, likely owing to the fact that Johnson was an American. Curiously, Johnson would go on to become an Oscar-winning Hollywood film producer and long-time collaborator of award-winning director Barry Levinson; it would be interesting to know how the younger Johnson found his way onto the Elios set in 1963, shooting a low-budget Euro-western. Also of note and credited as assistant director is Carlos Araud, who would eventually become a genre director in his own right, most notably working with Paul Naschy on a number of cult horror favourites (including El espanto surge de la tumba / Horror Rises from the Tomb [1973] and the 1974 giallo Los ojos azules de la muñeca rota/ Blue Eyes of the Broken Doll). Riz Ortolani’s score is mid-tier, fine if unremarkable, with none of the flare, flavour or daring he would bring to the form with his later work on, say, Day of Anger (1967 / Dir: Tonino Valerii).

The film opens proper in the Arizona town of Tombstone, where a guitar is gently strummed by Chirilo (played by José Canalejas, in a larger part than normal). Brandy, the town drunk, is tossed out of the saloon. Brandy is played by the American actor Alex Nicol. Whilst Nicol’s name might not be instantly familiar, he was with the Spaghetti Western from its genesis, more or less, having featured in Savage Guns (1961/ Dir: Michael Carreras), the first Euro-western to make proper use of our beloved Almeria landscape. Prior to that, Nicol had earned his western credentials in such American classics as The Lone Hand (1953), directed by the perennially underrated George Sherman, Redhead from Wyoming (1953 / Dir: Lee Sholem) and alongside Jimmy Stewart in Anthony Mann’s The Man from Laramie (1955). Nicol turned director in the late 1950s, helming the excellent independent horror film, The Screaming Skull (1958), before temporarily relocating to Europe at the dawn of the 1960s. He would follow his turn in Brandy by headlining the 1964 Spanish western, Relevo para un pistolero, alongside Luis Dávila and Aldo Sambrell. Nicol is solid as the titular character in Brandy, about as far away from the typical spaghetti western protagonist as one can possibly get.

Moody arrives at the saloon, clad in black, and offering Brandy a drink. Moody is played by Robert Hundar, an actor absolutely integral to the history of the European western. Although the genre would eventually see him relegated to villainous lieutenants in mostly supporting roles, Hundar was front-and-centre as performer when it came to the formalization of the Spaghetti Western, often as co-lead. Born in Castelvetrano as Claudio Undari, he moved to Madrid early on in his career, appearing in Cabalgando hacia la Muerte / The Shadow of Zorro (1962) for director Joaquín Luis Romero Marchent (the beginning of a long and fruitful collaboration) and paving the way for a ridiculously productive run in similar genre fare. (Much has been written about the influence of the early German Karl May / Winnetou adaptations on the European western, but the Spanish antecedents are less referenced and yet of equal importance in their imprint. The Zorro and El Coyote film adaptations which fed directly into the burgeoning Spanish – ergo, European – western craze were just as vital as Old Shatterhand and co. in their influence.) Hundar would go on to dominate such early entries as Tres hombres buenos / Implacable Three (1963), and El sabor de la venganza / Gunfight at High Noon (1964), both for Joaquín Luis Romero Marchent. Hundar would follow Brandy with the superb Sette del Texas/ Seven from Texas (1964), again for Marchent, and the ultra-rare but very enjoyable El hijo de Jesse James / Jesse James' Kid (1965 / Dir: Antonio Del Amo). He’s terrific in Brandy, a real bastardo, if a tad under-utilized (the film is crammed with many memorable villains – enough for two films).

Production design, credited to Galicia and Cubero (aka. José Luis Galicia and Jaime Pérez Cubero), is rock solid, very convincing. Tombstone feels like a real, hard-scrabble community, if admittedly a tad underpopulated. Chirilo puts down his guitar and enters the local gun shop, where the owner, Hopkins, has been threatened by local thugs for protection money. This is an odd, appealing subplot for a western, far more recognizable from various poliziotteschi films, in particular Enzo G. Castellari’s Il grande racket / The Big Racket (1976). The shop owner laments that if everybody took a stand like him, the town could overcome the criminal element. A strong-willed, pro-active merchant in a spaghetti western was a rare thing, although one suspects that such admirable-yet-foolhardy belligerence might cost him dearly. Sure enough, having distracted Hopkins, Chirilo then blows-up the entire store using a stick of dynamite procured from Moody. This is wonderfully captured on film, with Canalejas running from the building and rounding the saloon in real time, just as the place explodes behind him, in-camera, with no apparent cuts or fakery. In an age of ridiculously unconvincing CGI explosions, the old-school, practical, in-camera art of destruction continues to grow ever-more impressive. Amidst a downpour of debris and a swathe of black smoke, Moody vacuously laments the death of Hopkins, blaming the stockpile of explosives within the establishment. Hundar belongs to that small coterie of SW regulars – the likes of Gianni Garko, Piero Lulli, Fernando Sancho, Roberto Camardiel – who could convey a moral dexterity and play both ways, hero and villain. Just like the viewer, the sheriff smells foul play, and proclaims the act to be one of murder. Sheriff Clymer is played by the terrific Antonio Casas, so good in Duccio Tessari’s Ringo diptych. Like fellow spaghetti western alumni Aldo Sambrell, the Galicia-born Casas was a former professional football player-turned-actor, having played for Atlético Madrid in his younger years. He’s excellent here, playing the just and honourable lawman of Tombstone, although the viewer might well wonder why Clymer has no sworn deputies.

Hopkins’ charred body is lifted from the demolished site, tended to by the town pastor, who, along with the lawman, laments the infestation of crime in their fair city, suggesting this act of violence is a known quantity, the town in the grip of something rotten. Pastor Andrews is played by the great Renzo Palmer. Palmer was never a presence in the European westerns, but the prolific actor went on to appear regularly in many poliziotteschi films, including the aforementioned Il Grande Racket. It’s nice to see Palmer out west. Brandy, drunk and unfocused, vouches for Moody, through one gets the feeling this is more out of plain, drunken naivety than any form of overt collusion. The sheriff threatens Moody further, but it’s clear that Moody is – like many crooks, on film as in life – protected from on-high by unscrupulous men of dubious power. It’s a great opening, establishing real menace and threat whilst highlighting the plight of the townsfolk. The man at the top in Brandy is David ‘Beau’ Pritchard, your typical unscrupulous type played here by George Rigaud. The Argentinian Rigaud was a mainstay in French and Italian cinema, racking up almost 200 film credits in a long and distinguished career, and is most recognizable today to genre film fans for his many gialli appearances. He makes for a solid, eminently hissable bastard (who, hilariously, hates to be called ‘Beau’). With Hundar, Casas, Palmer, and Rigaud, Borau’s film has a stacked cast of world-class talent amongst its ensemble players.

The film then deviates and picks up on a secondary narrative thread: that of Steve Donnelly being released from prison. Donnelly is played by Luis Induni. Is Donnelly our hero? He seems to be on the usual hero’s journey, looking for redemption and/or peace. Donnelly is taken back into town by a female landowner, Alex McCormack (Natalia Silva), who hopes that he hasn’t “Come back for revenge for what they did to him”. Does the film have the bottle to forgo the hip, younger, more handsome protagonist model for this – the moustachioed, middle-aged character actor? Has Induni finally been promoted to bona-fide leading man? We’ll see. The sozzled lush Brandy is especially pleased to see Donnelly back in town, although not everyone is that enthused. From the moment Donnelly sets foot back in the local saloon, Moody is nervous and jittery. The two men circle each other like stags, and we learn that Donnelly has just been paroled for a crime not committed, and that his new boss, Alex, is the biggest homesteader in the valley, and one of the last of the ranchers to capitulate to Pritchard and Moody’s tyranny. The inevitable violence is avoided at this early juncture, the film side-stepping the clichéd bar fight, at least for now.

The film then deviates and picks up on a secondary narrative thread: that of Steve Donnelly being released from prison. Donnelly is played by Luis Induni. Is Donnelly our hero? He seems to be on the usual hero’s journey, looking for redemption and/or peace. Donnelly is taken back into town by a female landowner, Alex McCormack (Natalia Silva), who hopes that he hasn’t “Come back for revenge for what they did to him”. Does the film have the bottle to forgo the hip, younger, more handsome protagonist model for this – the moustachioed, middle-aged character actor? Has Induni finally been promoted to bona-fide leading man? We’ll see. The sozzled lush Brandy is especially pleased to see Donnelly back in town, although not everyone is that enthused. From the moment Donnelly sets foot back in the local saloon, Moody is nervous and jittery. The two men circle each other like stags, and we learn that Donnelly has just been paroled for a crime not committed, and that his new boss, Alex, is the biggest homesteader in the valley, and one of the last of the ranchers to capitulate to Pritchard and Moody’s tyranny. The inevitable violence is avoided at this early juncture, the film side-stepping the clichéd bar fight, at least for now.

‘I bet you’ve been drinking,’ Donnelly says to Brandy, in a moment of brilliant psychological analysis. In what we must assume to be Ye Olde West equivalent of walking a straight line whilst touching your nose, Brandy climbs into the saddle and rides as if to proves his sobriety. (The horse bucks and kicks violently, always remaining in-shot, and it appears to be Alex Nichol himself doing all the riding, no stunt person or cutaways.)

The film continues to draw lines, dividing the town into two clear camps. Brandy, Donnelly and the Sheriff align themselves, although the sheriff fears he may-well be next in line for an ‘accidental’ death. In a superfluous but brief and welcome aside, we get to see the sheriff doing a bit of admin work, explaining his unlikely filing system to a curious, would-be-deputy teen, Chico (Johnson). Curiously, one of the wanted posters is for Tombstone’s own Pastor Andrews; a tantalizing prospect that is – oddly – never referred to again. Meanwhile, Eustice Underhill, the town’s pompous banker, reveals to the town a brand-new, state of the art safe, in which, he promises, “All your money will be safe”. The citizens of Tombstone look on, broke and penniless, their blank expressions hilariously dismissive of this fat cat and his new toy. Underhill invites everybody back to the saloon, and offers the sheriff a drink, but the honest lawman refuses. Brandy, however, has no such scruples, and is soon licking excess booze off his hand like some kind of animal. At the twenty-minute mark, the film offers no real hint as to its hero. The sheriff and Donnelly are proving to be two hugely likable characters – played by two hugely likeable actors – but both seem doomed by way of virtue and morality. Brandy, however, is an enigma, albeit not an especially interesting one; irritating, blind to the corruption around him and bordering on a clownish, woefully unappealing countenance.

Underhill is so sure of his impenetrable new safe that he announces his plan to leave his bank open all night, should anyone fancy a crack at it. At this juncture, the film’s narrative takes a sharp left turn, when Brandy fools Underhill into opening the safe and then summarily robs him at gunpoint. (Hilariously, Brandy then forces the banker to change a bill into coins in order to buy a cigar from him.) Hailed a local hero for having opened the safe via intellect and guile, Underhill attempts to have Brandy arrested for robbery. To be fair to Brandy, he selflessly pours the money back into the local economy by blowing it all at the saloon. There follows a horrendous song-and-dance sequence which is mercifully cut short when the saloon boss catches his barmaid, Eva, stealing from the till. Pleading poverty (she owes the taxman), Brandy consoles her in an insipid sequence stuffed with inconsequential dialogue (during which Brandy reveals his real name to be Robert, killing what little mystique remained). Meanwhile, on the outskirts of town, Chirilo threatens a farmer for yet more protection money, but the proletariat refuses to pay, prompting further carnage. As Moody and his riders converge on his land, the farmer and his men fend them off in a routinely competent gunfight before the place is finally burned down. Again, in an age of cheap, unconvincing computer generated imagery overstatement, there’s something viscerally hypnotic about a set burning in real time.

The town fathers meet and condemn the sheriff, a paragon of virtue in a town gone to shit, and obvious obstacle with regard to their spreading tentacles of corruption. They talk of historical deceits, intimating that evil is akin to any skill – requiring only practice and commitment. Even in the politically biased world of the spaghetti western, there is a dirty specificity at play here, and it marks this lot as a very special kind of scum. They even refer to their criminality as an operation – a legitimate coalition of corrupt businessmen, a transparent facsimile of the mafia. To them law & order isn’t a moral imperative, rather a façade on which to supress and – more importantly – profit. Hell, maybe the privatization of police began here, in Tombstone. The viewer demands justice, hopefully via Pritchard and his co-conspirators’ deaths, but the film is still without a hero figure, save a charmless booze hound, a neutered ex-con and a decent – albeit doomed – lawman. Where is our Stranger? Our Django? Our Ringo? Over halfway in, and the film offers nothing by way of an avenging rider. The townsfolk are good, decent people but they are also portrayed as simpering idiots, oblivious to the fate befalling them. At one point, the sheriff picks up a guitar and begins to sing, the scene clearly a homage to Wayne, Martin, Brennan and Ricky Nelson in Rio Bravo, but whereas the characters in Hawks’ classic came across as cool, patient and laconic, this lot merely register as naïve fools. Seconds later and the sheriff is dead. The judge looks to elect a replacement, suggesting that he, too, is on the level and untainted by corruption. “This town needs a sheriff with guts who can outdraw anyone,” he tells his constituency.

So does the film.

There is more interminable romance between Brandy and Eva, which I’m prone to skip over. The Italian westerns never quite nailed the whole love thing. There’s nothing wrong with prairie romance, but it must be done right, as an extension of the drama/action, as opposed to secondary plot point that slows down all momentum. Think of Barbara Stanwyck’s torrid passion for Gilbert Roland in Anthony Mann’s The Furies (1950), or her violent affection for Barry Sullivan in Sam Fuller’s Forty Guns (1957) – both relationship arcs as incendiary and exciting as any action beat in either film. Of course, Silence’s gloomy love for Pauline in Il Grande Silenzio (1967) is achingly rendered, but for the most part, the Euro-westerns were unsure what to do with love, and for the most part played it safe. Leone was wise to eliminate lust and desire from his hero’s manifesto, rendering the cowboy asexual and mitigating all unwelcome emotional entanglements.

Donnelly and Moody exchange harsh words. Could Donnelly be the film’s secret weapon? Could this be Induni’s moment of glory? This long-standing character actor – often limited to minor supporting roles, invariably as a lawman – certainly deserves a shot at the title, but will the film play fair? At this point in the film, Induni’s Donnelly seems to be the closest thing Brandy has to potential saviour. It’s looking good – Induni gets his very own fight scene, taking on multiple assailants with his fists, and sells it all wonderfully. Induni throws a couple of decent punches and moves convincingly, suggesting a hitherto undemonstrated physical prowess. Any hardcore spaghetti western fan should get a real kick out of this sequence; Induni is well deserving of the spotlight and the actor reveals himself to be a pretty tough hombre. This really is an unexpectedly great action set piece that erupts out of nowhere and threatens to be memorable, worth the price of admission alone. Why, then, one asks, was this entire sequence cut from the Spanish version, as noted above? In terms of physical action, it’s the centrepiece of Borau’s film.

Just as Donnelly is about to concede to the overwhelming odds, Brandy intervenes. Donnelly offers to buy Brandy a drink by way of thanks, but Brandy turns it down. “I no longer drink” he says, slipping into a newfound sobriety as if it were a new coat, seemingly unafflicted by crippling withdrawal sickness or debilitating tremens. One can’t help but wonder if the film might have benefitted from an extended cold turkey sequence; Brandy chained to a bed, sweating out his demons in real-time agony à la Gene Hackman in French Connection II (1975). Now that would have been something.

The young deputy Chico is shot and killed by Moody, which sends Brandy spiralling ever-more into cold, hard sobriety. As the fog of alcohol clears, Brandy begins to see the violent depravity strangling his beloved town, such stark realization the very worst kind of hangover. After this, the crooked politicians realise that they now have the perfect new candidate for sheriff in Brandy (easily manipulated and motivated by malleable addiction). Pastor Andrews calls them out on their reasoning for wanting Brandy elected. A pro-active priest in the spaghetti western was rare; the genre was often used as a condemnation of the church, or at least as a conduit of complaint for many leftist directors. Whilst Donnelly teaches the still-sober Brandy how to use a pistol, the ballot reveals Brandy to be Tombstone’s newly elected sheriff. Wasting no time, or, perhaps, making up for lost time, Brandy takes a warrant and confronts Moody. When Donnelly involves himself, Moody draws, but is outgunned by the older man. Sadly, Donnelly is gunned down moments later by the devious Chirilo. With just 12 minutes left on the clock, Induni exits the picture. Brandy hits the vengeance trail, although remains a deeply unconvincing presence with regard to legitimate threat. In Tequila Joe, Anthony Ghidra’s titular lush was a former gunman and a prize-winning sharpshooter, his skillset tempered by the bottle, sure, but suppressed deep within, just waiting to be summoned and put back to good use. But Nichol’s Brandy has no such reserve, no history of violence, and so never entirely convinces.

Stalking Chirilo over a horizon of dangerous-looking rock formations, Brandy eventually throws Donnelly’s killer off a butte top, rewarding the viewer with a terrific dummy death. The banker attempts to flee, fleecing the town fathers, but is caught and forced to stay when Pritchard reveals he has called on a band of hired killers to go up against Brandy. Cue the town’s final stand, with the honest citizens fighting back, roused from their fearful apathy by the death of their beloved sheriff. Even Pastor Andrews partakes in some good ol’ fashioned killing (although, given his appearance on a wanted poster earlier in the film, this proves a missed opportunity to clarify that particular narrative strand, which remains abandoned).

The dénouement rings hollow and is oddly unsatisfying. Brandy wins Moody in the climatic brawl not because he’s the strongest or smartest, or because his character has earned said victory, but because the screenplay says so; because the film demands a neat, audience-friendly conclusion. I don’t buy it. Moody may be a thug, but he’s a physical beast, a killer. Brandy’s ultimate defeat of Moody carries no weight or impact. It’s nothing more than a narrative get-out clause. Does that undermine Borau’s film, though, or make it any less enjoyable? No, not at all.

On first viewing, especially in a print of dubious picture quality, it’s easy to dismiss Borau’s film as a staid, distinctly average oater of the would-be-American mould, but – after multiple viewings in advance of this review – I’m not so sure that’s the case. As a whole, Brandy exhibits none of the flair or audacity that we have come to associate with the best of the Spaghetti westerns. There is little subversion of either form or audience expectation, nothing ground-breaking about its narrative path or technical execution (although the camera work is often fluid, restless, frequently in-motion), but the film is very well mounted and peppered with memorable moments that, whilst seemingly unremarkable at the time, linger long in the mind. And as much as I love the genre, many European westerns were/remain indistinguishable by way of basic plotting and middling energy; Brandy, however, distinguishes itself slightly through tone and Borau’s careful attention to detail. His only western, Borau genuinely seems to care about his film and the characters that inhabit it. Whilst many spaghetti westerns limped blindly from action scene to action scene, the filmmakers fearful of losing the viewer’s attention in-between, Borau invests throughout, ensuring his connective tissue is just as thrilling as his gunplay. Borau is also the credited screenwriter (based upon the story ‘The Sheriff of Tombstone’ by José Mallorquí), which further validates his investment in the material.

Brandy works remarkably well, then, when all is said and done. It feels different to those other prototypical westerns being produced around that same period, although it’s hard to articulate why, which makes it all the more disappointing that the film isn’t more well known. Had the film a stronger presence in the lead, perhaps, then maybe Brandy would enjoy a stronger reputation. But perhaps I’m missing the point; Alex Nicol was a good actor (his villainous turn in Savage Guns could hardly be more different to his placid, good-natured performance here), and maybe it’s his wispy, wallflower performance here that makes the film so effective: whilst Brandy’s ultimate victory might not wholly convince, likewise, not for one moment do Pritchard, Moody or Underhill ever acknowledge him as a legitimate threat to their enterprise. And so, whilst his eventual stand might not surprise the viewer, it certainly comes as a shock to those who sought to manipulate and control him. The moral is simple, the lesson plain: underestimate this character at your peril. The same could be said for Borau’s film itself.